On October 20, 2025, the internet blinked. Amazon Web Services (AWS), the cloud engine behind much of the modern web, went offline for several hours. Banks, delivery apps, smart devices, and gaming platforms stalled.

Across Africa, users in South Africa, Nigeria, and Kenya noticed apps failing to load and payments hanging mid-transaction. What began as a system error in the United States quietly rippled through a continent that now runs much of its economy online.

AWS powers everything from fintech dashboards to government portals. So when it fails, the downtime hits beyond technology. For startups chasing customers and investors, those missing hours translate to lost trust and frozen activity.

What Happened and Why It Matters

The outage began in AWS’s US-EAST-1 region, its busiest hub. A DNS malfunction broke communication between servers, cutting off access to major platforms including Snapchat, Ring, and Fortnite, according to Reuters and The Washington Post.

Although the problem was thousands of kilometres away, its effects travelled fast. African startups using AWS-hosted tools saw dashboards freeze and payment systems time out. Customer support and automation pipelines stopped mid-process.

Most African traffic passes through AWS’s Cape Town region, opened in 2020, which connects local data to global servers. That setup is efficient but fragile. A single fault in one region can slow another without warning.

For developers across Lagos, Nairobi, and Accra, the incident reinforced a simple truth: Africa’s internet boom still depends on infrastructure outside its borders.

The African Dependency Problem

Africa’s digital economy runs largely on foreign servers. Apps, fintech dashboards, and e-commerce sites across the continent sit on infrastructure owned by AWS, Microsoft, or Google. When one of them falters, the impact extends far beyond a single data centre.

AWS’s footprint remains centred in South Africa, where it opened its first regional hub in Cape Town in 2020. The rest of the continent connects through that hub or directly to data centres in Europe and the United States. It works well until something breaks upstream.

During the outage, MyBroadband and Intelligent CIO Africa reported spikes in downtime across South African networks. Some services slowed even though their local servers were fine. Startups elsewhere on the continent, with no regional backups, went offline entirely.

African founders choose AWS because it is stable, scalable, and affordable compared to local options. The trade-off is control. A single outage far away can freeze payments, disrupt data, and stall operations.

The event has revived calls for digital sovereignty, more local data centres, stronger regional connectivity, and contingency plans that reduce reliance on one global provider. When the cloud sneezes, the continent should not catch a cold.

Impact on Business

For ordinary users, it looked simple: websites wouldn’t load and payments failed. For African businesses built on AWS, those hours were costly.

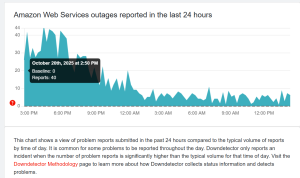

Outage trackers such as Downdetector South Africa logged sharp increases in error reports through the afternoon. Local startups using AWS-based payment or logistics systems saw interruptions. Developers shared screenshots of failed transactions and backend errors on X, while founders reported dashboards stuck in loading loops.

Banks and telecoms, which use hybrid setups mixing cloud and on-premise servers, recovered faster. Smaller startups, SaaS tools, and digital media sites faced longer delays.

By evening, AWS’s status page confirmed the DNS issue had been “fully mitigated.” Services resumed, but the brief blackout left its mark.

Lessons and Takeaways

The outage lasted only hours, but it revealed how fragile Africa’s digital foundation still is. Startups and service providers have embraced the cloud, but few have built the resilience to survive when it goes down.

Most rely on AWS because it is dependable and easy to scale. That convenience hides a single point of failure. A growing number of African engineers now argue for multi-cloud strategies, spreading workloads across AWS, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud to avoid total downtime.

New investments by Liquid Intelligent Technologies and Africa Data Centres are starting to localise infrastructure, offering an alternative path that keeps services closer to users.

Governments can help by encouraging data-hosting infrastructure, open peering, and cloud diversity. As Africa’s economies move online, internet stability becomes an economic priority, not just a technical one.

When AWS went dark, it was brief but revealing. The world’s biggest cloud stumbled, and Africa felt it. The next step is ensuring that when it happens again, the continent keeps running.