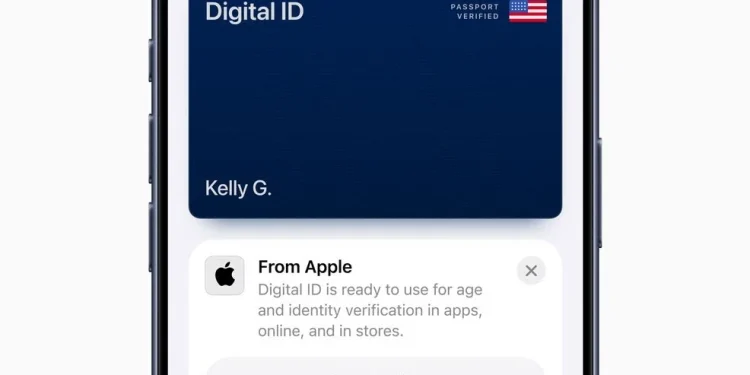

Apple’s push into digital identity feels inevitable. The company has spent years turning the iPhone into a payment tool, a health card, a car key, and, most recently, a digital ID tied to a user’s passport. But the introduction of Digital ID raises deeper questions about necessity, value, and the trade-offs consumers are being asked to accept.

A Convenience Built on Existing Friction

Apple’s pitch is simple: storing a digital version of your passport or ID in Wallet makes verification faster and more secure. For domestic U.S. travellers, the idea of tapping an iPhone instead of handing over a document sounds convenient.

Yet the convenience rests on a limitation Apple didn’t create but now builds upon. Airport security lines are slow because verification systems are outdated. Rather than modernise the process universally, Digital ID introduces a solution that only works if you are already inside Apple’s ecosystem. Convenience becomes conditional: you benefit only if you use the right device, update the right software, and trust the right company.

The Gap Between Promise and Practical Use

A major critique is the narrow scope of Digital ID. It does not replace the physical passport, cannot be used for international travel, and functions only at selected TSA checkpoints.

Apple presents it as a step toward the future, but in practice, it solves a problem for a small slice of users in tightly controlled environments. For most people, the physical ID remains the one they must carry anyway. The digital version becomes an optional add-on rather than a true replacement, weakening the case for adopting it widely.

Identity, Privacy and the Power Trade-Off

Apple highlights encryption, local storage, and limited data sharing. These are strong features, but they don’t resolve a broader concern: identity is becoming another layer of digital infrastructure controlled by large technology firms.

Digital identity is fundamentally different from storing cards or tickets. It carries legal, biometric and travel implications. When a private company becomes a gatekeeper for that information, even with good intentions, it centralises power in ways that governments and regulators have not fully addressed.

There is also the question of long-term risk. If digital ID becomes widely accepted, opting out may eventually feel impossible, not because it is unsafe but because refusing to participate removes you from systems built around it.

A Future That Isn’t Equally Distributed

Digital ID may work for frequent fliers in North America, but the concept offers little to users in Africa, South America or parts of Asia, where ID infrastructure differs and government partnerships are limited. The feature becomes another example of technology designed for one context and marketed as global progress.

Until digital identity is supported across borders, industries and regulatory environments, its social value remains uneven. Apple’s announcement reflects ambition, but the impact stops at the boundaries of countries willing to embrace the model.

A Step Forward, But Not Yet a Turning Point

Digital ID in Apple Wallet is a polished idea built for limited use. It demonstrates how identity could work in a digital-first world, but it also exposes gaps in readiness, policy and global applicability.

The technology is impressive. The execution is cautious. And the purpose, for now, feels less like a solution to a widespread problem and more like a controlled experiment in reshaping how we prove who we are.